Franklin Square

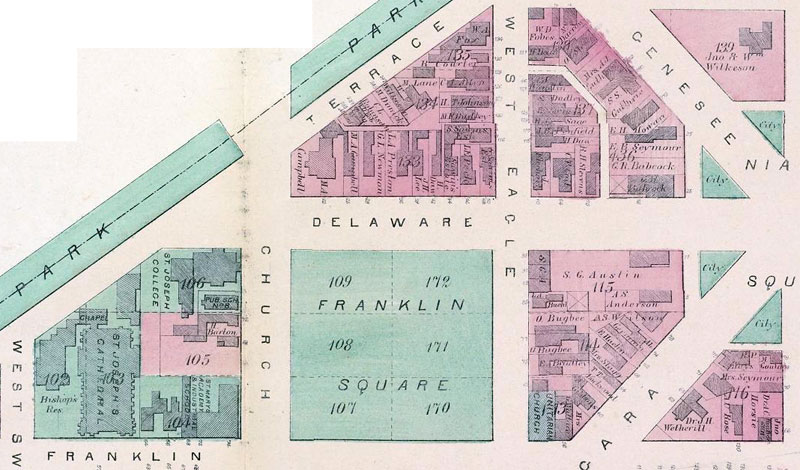

1854 Hopkins Atlas showing Franklin Square. Image source: NYPL

The plot of land bounded by Franklin, Church, Delaware and Eagle Streets was not designated by Joseph Ellicott as a square when he drew the streets of Buffalo. The land in 1804 was part of the Terrace, the high ground that provided a panoramic view of the Niagara River and Lake Erie. It was grassy, with trees here and there. Buffalo resident William Hodge said in 1879 that he recalled Native Americans reclining there to enjoy the breezes from the lake. William Peacock, Holland Land Company surveyor and land agent, said "It is one of the most beautiful views I ever put my eyes on."

Early residents of the village of Buffalo buried their dead on their own properties or used a burial plot set up on the Johnson property on Seneca and Washington street. But Captain Samuel Pratt and Dr. Cyrenius Chapin foresaw problems with this practice as the population increased, so they traveled to Batavia and received verbal approval from Ellicott to use the land described above as a burial ground for the village. People who wished to bury a relative were assigned a lot but did not purchase ownership rights. In 1821, formal title for the cemetery was granted to the village by the Holland Land Company.

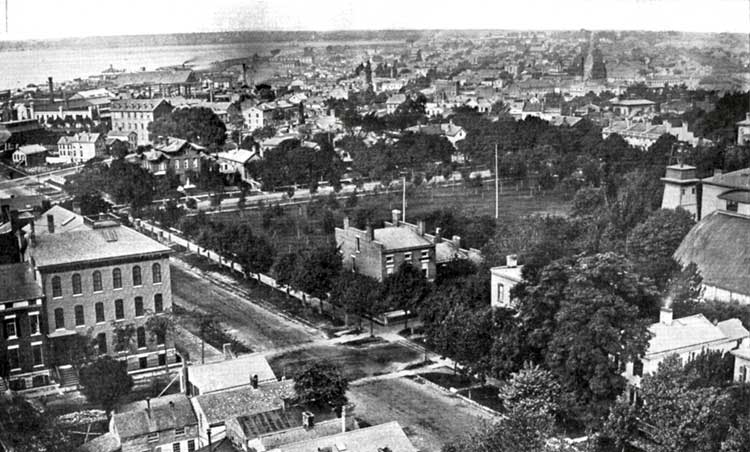

Franklin Square in 1870. Church Street at left. Image source: NYPL

The Franklin Square Cemetery would figure large in Buffalo's early history for two reasons. First, on December 10, 1813, the British were making their way to the village, having burned every settlement along the Niagara Frontier from Lewiston south. Dr. Cyrenius Chapin, in an attempt to buy time for the Buffalo residents to escape, attempted to surrender to the British commander, General Riall, at the Franklin Square cemetery. It was soon determined that Chapin was not the American commanding officer, and the British commenced torching the village and killing its residents.

After the British and their Native allies eventually left the village, the Franklin Square cemetery served its original purpose as the burial ground for dead American soldiers and civilians.

Wider view of Franklin Square, c. 1870 Image source: Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo

The cemetery continued to be used, even by people who had moved to outlying areas, until 1832 when the area suffered a cholera outbreak and the new city administration feared transportation of diseased corpses through the city. Franklin Square cemetery was closed, but a special permit was issued in 1836 to Samuel Wilkeson, former mayor and harbor builder, that allowed him to bury his second wife, Sarah St.John, daughter of Margaret St. John, whose home/tavern was the only residence not burned by the British in 1813.

The cemetery was not maintained by the city or any association. Elizabeth Leavitt Keller recalled regularly crossing through the cemetery to get to School 6 and said that it had become overgrown with weeds and sweet briar bushes. After the city had graded the surrounding streets, the cemetery was higher than the surrounding area and had to be surrounded by a stone wall.

Then, in 1849, a new cemetery was created at the northern edge of the city, Forest Lawn. Three years later, in 1852, all of the remains were removed from the Franklin Square cemetery and re-interred at Forest Lawn. Many of the 1158 dead had no headstones. Franklin Square became a small park in the midst of the growing city.

A few years later, the city of Buffalo received a $40,000 bequest from the estate of Seth Grosvenor for a library and there was talk of utilizing land on Franklin Square for this. That was not approved and the square remained unchanged until 1870, when the city determined to build a new city hall on the land.

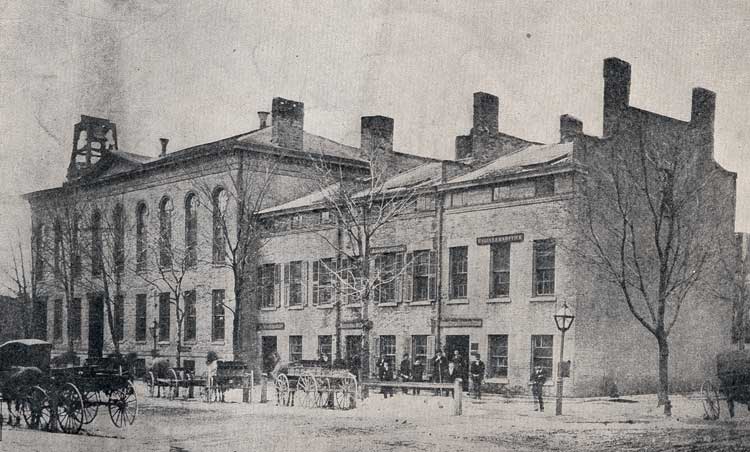

Image source: Express Yearbook

The above buildings, located on the corner of Franklin and Eagle Streets, were used for city and county offices from 1852 until being demolished for the construction of the new city hall on Franklin Square.

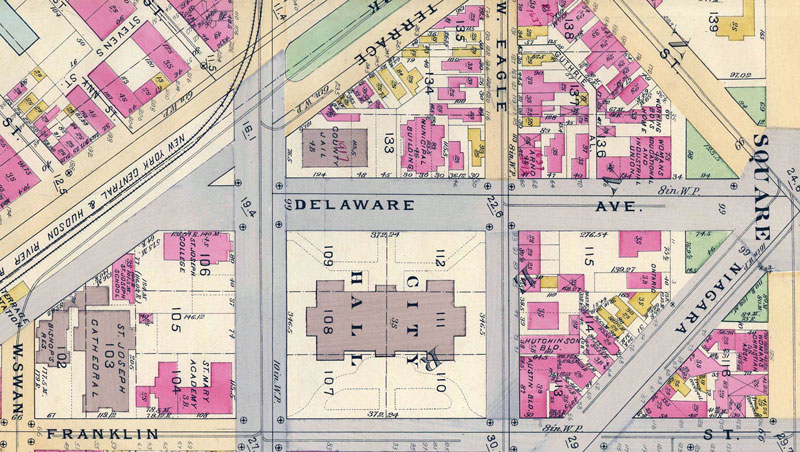

1894 Buffalo Atlas

Mrs. Keller said, "It hardly seems possible that a place once appearing so immense can be covered by the city hall, the small grass plots and sidewalks surrounding it." The new city hall, which also included county offices, opened in 1876.

City and County Hall when new. Image source: NYPL

In 2013, the building is called Old County Hall, and has been enlarged by a modern addition on the Delaware Street side.

Image source: Library of Congress HABS

Forest Lawn 2013

A large square plot contains the remains of those buried at the Franklin Square cemetery; the handful of gravestones are set around the border. The monument in the center was installed in 1862, ten years after the reinterments. One side memorializes the military men who died during the War of 1812. One side states that the remains of Farmer's Brother, Ho-na-ye-wus, are buried here. The Native American, 80 years old at the time of the War of 1812, was the leader of the Native allies of the Americans and was revered by both nations. He died March 2, 1815 and was buried at the Franklin Square cemetery with full military honors.