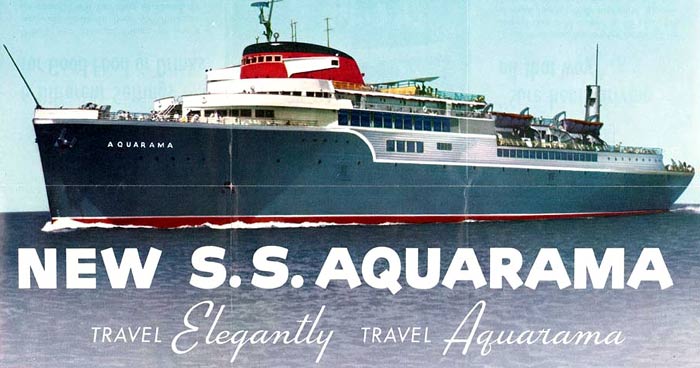

The Marine Star - AKA The "Aquarama"

Born in 1945 in Chester, Pennsylvania, as a World War Two troop ship, the future Aquarama was named the Marine Star. She made one Atlantic crossing before war ended and with it her usefulness to the U.S. Maritme Commission. The ship was mothballed until 1952 when it was purchased by the Sand Products Company of Muskegon, Michigan.

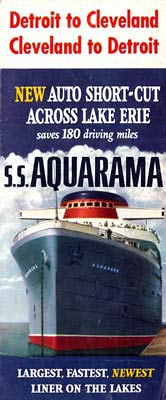

Company President Max McKee envisioned a market for an elegant "ocean liner on the Great Lakes" that would quickly move people and their automobiles between Detroit and Cleveland. He spent $8 million dollars to have the ship converted in Brooklyn and Muskegon. It was the first new liner on the Great Lakes in 20 years; passenger traffic had been continuously declining.

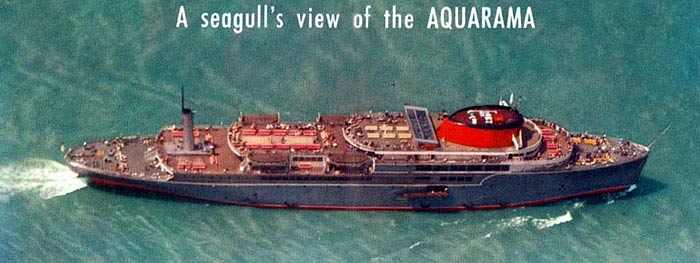

When completed, it was an impressive sight. Corrugated stainless steel siding added a sleek look to the sides and evoked the latest design of train passenger cars. The bright red dummy smokestack in the center housed the quarters for the ship's captain and officers. The actual smokestack of the oil-fueled ship was located far astern to eliminate smoke and soot from bothering the passengers.

The ship featured nine decks, two of them for automobiles, and no cabins for passengers. This was to be a day-trip ship.

The newly-named Aquarama (selected as the winner in a contest to name the ship) was the biggest passenger vessel on the Great Lakes. It was 520' long (almost a city block), seven stories high, 71' 6" at the beam. It displaced 10,600 tons (the same as a Navy cruiser), and had a 21 1/2' 10-ton bronze propeller with a 22" diameter steel drive shaft. Its speed was rated at 9,000 HP, and its cruising speed was a swift 22 knots. It may have been transformed into the Aquarama, but it was built for ocean travel and spaces. That fact would prove to be a problem as it tried to navigate the Great Lakes ports.

The Aquarama first sailed in July, 1956, having been leased in 1954 to the Michigan Ohio Navigation Company for service between Cleveland and Detroit. Its first schedule called for a trip from 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. and an evening cruise from 7:00 to 11:30 p.m. Ticket prices ranged from $2.50 to $4.75; children under 12 sailed for free.

The company widely publicized the safety features of the ship (to allay fears that some might have had because the Andrea Doria fire and sinking were fresh news). So they advertised the all-steel construction (except for the dance floors and ervice bar tops), the 24-station smoke detection system, auto fire-enclosure doors, and four 135-passenger lifeboats. (The boat was said to be able to carry 2,500 people and 160 automobiles.) The latest in radar, radio-direction-finder, and closed circuit television for viewing the stern et al would come in handy during its short career in Great Lakes harbors.

The Aquarama was able to dock downtown in Cleveland and Detroit at exisiting dockage facilties, something they advertised as a convenience. But the design of the ship itself offered many passenger-pleasing conveniences. Customer-service areas included an open-counter ship's office, baggage check, novelty and cigar shops all located near the main stairs.

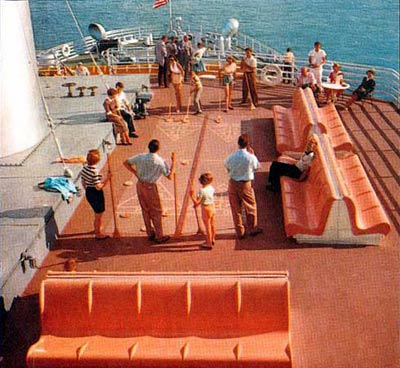

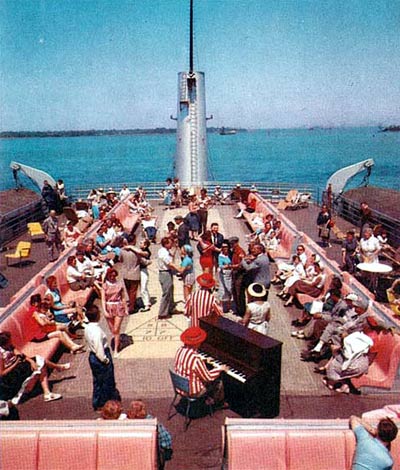

Passengers enjoyed the spacious public spaces, inside and out. The two Westinghouse escalators were the first on a Great Lakes ship and, with the elevator, were capable of moving people quickly and effortlessly around the ship.

There were two observation lounges enclosed by large, heat-absorbing tinted windows. Marine motif murals by Pierre Bourdelle added to the festive interior. A crew of 189 (53 operating, 136 stewards) provided support services for the passengers.

There were two dance floors, with a raised orchestra platform/shell.

Thre was a carnival room containing a giftshop, novelty games, photo booth and a voice recorder.

A playroom had baby-sitting services for children aged 2 - 6, a tricycle, blackboard, books, toys, a flashing lighthouse, and a small model of the Aquarama with a kiddie-operated steering wheel.

There were four restaurants of varying styles and charges. The main cafeteria could seat 300 people. Two television theaters (seating 66 and 86) could also be used for conferences or special programs.

The ship's origin as an ocean-going cargo vessel with the corresponding size and power of such a ship created problems for its navigation in the harbor rivers and docking from its first sailing. The ship, never loaded heavily enough to sit appropriately low in the water, behaved like a sail in high winds and trips were delayed or cancelled a number of times due to wind. The winds and inertial speed of the ship caused it to bang into the Detroit News dock, ram into the seawall in Windsor, and bump into a Navy cruiser in Cleveland. Having only one propeller made manuevering in small spaces challenging. And the enormous wake it left behind even at low speeds swamped numerous boats, causing considerable damage and nearly costing a child its life.

Despite numerous changes in its schedules, the Aquarama did not consistently make enough money to be self-supporting because excursion travel by boat was becoming passe. Around 1963, a potential deal to have the Aquarama replace a car-passenger ferry in Wisconsin fell through because Milwaukee declined to pay the $700,000 dredging costs necessary to accomodate the Aquarama. And so the Aquarama was laid up in Muskegon, Michigan until 1987, when it was purchased by the North Shore Farming Company of Port Stanely, Ontario. The selling price was rumored to be around $3 million dollars.

First, the Aquarama was towed to Sarnia, then to Windsor where it was thought to have a future as a floating casino. But legal obstacles prevented this and, in 1995, the ship reverted to its first name, the Marine Star, and arrived in Buffalo on August 3, 1995. For 10 years, it was berthed at the Cargill Pool Elevator on Fuhrmann Boulevard. The owners, the Empire Cruise Lines of Delaware, paid $60,000 per year in maintenance, docking, and insurance fees. Its value as scrap was estimated at $1 million dollars. The interior furnishings were largely removed during its years in Windsor. It departed Buffalo in July 2005. It was towed to Turkey to be cut up for scrap.

Many thanks to Bjorn Larsson for granting permission to use his image scans of an Aquarama brochure. Ship details also used from Ladies of the Lake II, by James Clary