Katherine Bell Lewis: Suffragist & Philanthropist

Katherine Bell Lewis is one of Buffalo’s lesser know suffragists today. She was nonetheless among the best-known and admired women in Buffalo’s progressive community for her participation and philanthropy during the early 1900s. Born in Nunda, New York, in 1848, Kate (as she was known to her friends), was the 4th of 5 siblings born to Alfred and Juliette Bell. She became acquainted with loss early; three of her siblings died young. Her only sister, Julia, died at age 17. Her family did not begin with wealth but her father, who had emigrated from Vermont, purchased a tract of timber land in Pennsylvania. After the timber was removed and sold, the land was found to have a rich vein of coal. In 1870, the family moved from their large Nunda home to the city of Rochester. Young Kate was sent to Batavia to attend Mrs. Bryan’s Seminary; classes were held in the vacant Holland Land Company offices (now the Holland Land Company Museum). When finished with her finishing school, she returned home to Rochester where she remained single until age 26, several years past the average age of marriage at that time. She was introduced to a 35 year-old man who had already begun his career in Montreal. Like her father, he was reserved and without pretension. A Buffalo columnist described him as a “singularly handsome, aristocratic looking man, of the type known as a gentleman of the old school.” |

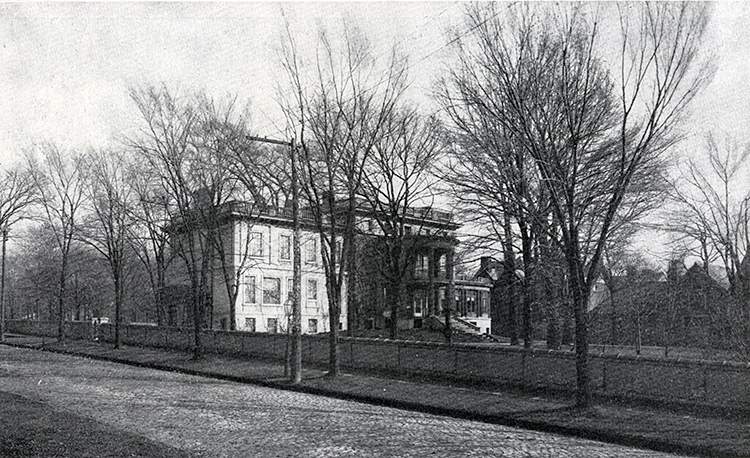

They married in 1874 and lived for a time in Rochester, where Kate was engaged in the hobby of microscopy. Amateur microscopists investigated the world of cells, membranes, organisms by using a microscope. They often drew images of their observations and met with like-minded hobbiests to compare their findings. She apparently pursued this hobby from 1874-1879, until she and George moved to Buffalo. That year, they purchased the old Efner mansion at 656 7th Street on Buffalo’s West Side. It was named Elmstone for the large elm trees surrounding the lot and the Lewises retained that name. Look here for the story of Elmstone.

Elmstone viewed from Front Street. Image source: Picture Book of Earlier Buffalo

George H. Lewis had formed a company with his brother-in-law Frederick Bell and Arthur G. Yates in 1876. Bell, Lewis & Yates was in the business of owning Pennsylvania coal fields and shipping the coal to Buffalo and Rochester for transshipment. The relocation to Buffalo was sound business practice because the city was the center of lake, canal, and rail transportation. The company grew throughout the 1880’s until it was the largest owner of Pennsylvania coal mines. One historian claimed that the company “practically owned the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh railroad” because of the volume of coal it shipped. In 1883, 100 coal cars were shipped every day. By 1885, Buffalo was the third largest coal depot in the U.S., handling nearly all of the country’s anthracite and a growing share of its bituminous shipments. It seems an understatement to say that George and Kate acquired a great deal of money during the 1880s and 1890s, a time of tremendous growth in American industry with its appetite for coal and coal products. The couple had a son, Alfred, in 1879. And in 1881 they suffered the loss of a second son at about 8 months of age. They significantly expanded Elmstone, adding on two sides of the old mansion, including a large conservatory. They both enjoyed flowers – George was an orchid fancier – and created a tropical world in the conservatory that included fountains. George was a director of The People’s Bank and also a director of the General Electric Company. Quietly, he involved himself in local charitable activities with particular emphasis on assisting children’s causes that included the Newsboys and Bootblacks Home. In 1895, he organized a relief fund to aid Buffalo’s poor that raised $60,000 ($2,231,072 today). |

Niagara Hotel, Porter & 7th Street. Image source: Internet

George also decided to build a fine hotel because he had visited Europe and wanted to replicate the atmosphere in Buffalo’s West Side, not far from Elmstone. Buffalo had no luxury hotels in the 1880s. He had the disposable income. He hired Green & Wicks, one of Buffalo’s major architectural firms, to build his hotel. It opened in 1888 on Porter and 7th Street as the Niagara Hotel. Look here for information on the Niagara Hotel.

And then, in 1897, Kate’s life was altered forever. Her husband, 57 years old, died suddenly of heart failure at home. She and 18 year-old Alfred were by his side. After funeral services at Elmstone, his body was sent to Rochester by special train for burial in Mount Hope Cemetery. Within a span of 8 years, she lost her father, mother, husband, and only surviving sibling, Frederick. Buffalo papers published encomiums regarding George’s excellent business mien and extensive philanthropy.

The first change she made was with the Niagara Hotel. She closed it in April 1898 and refused to lease it to any management that would serve liquor. Then, in 1900, she sold it to parties interested in capitalizing on the coming Pan-American Exposition.

Alfred Lewis expressed to his mother that he wanted to be a farmer. In 1898, his mother purchased White Spring Farms in Geneva, New York. When he reached 21, she signed over the farm to him. (And, in 1905, she purchased a farm not far from White Springs Farm, and named it Bellwood.)

As a 49 year-old widow, with a grown son and plenty of money, Kate Lewis slowly began to move about her world without the social restrictions wives often had. The first public indication of her new independence was her investment in Mary Remington, a settlement worker employed by the First Presbyterian Church in its new Welcome Hall at 404 Seneca Street. Miss Remington’s relationship with the church became strained, likely because of her rigid temperance stance, and after 1898 she and the church parted ways. Her intention was to establish her own settlement house in the Canal District, among the most destitute and largely immigrant population in Buffalo. Enter Kate Lewis. Upon Miss Remington’s resignation from the church’s settlement, Kate gave her $600 (nearly $23,000 today). Then, when Miss Remington opened her Remington House in the old Revere Hotel at Canal and Erie Street, a further gift of $100 and plants from the Elmstone conservatory came to her. From 1898 – 1912, Kate Lewis sent an annual stipend of $600 to Miss Remington. Further, several years later, she gifted $1,000 to be applied to the Remington House mortgage. Then, when Jacob Schoellkopf, owner of the land under Remington House, insisted that Miss Remington purchase it, Kate Lewis assumed the mortgage at a rate much lower than the banks offered. All of this financial support ended in 1912 when, as Miss Remington summarized, Mrs. Lewis had to cease the annual payments and also required Miss Remington to assume the mortgage she had held. |

Buffalo was the location of the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s conference in 1908. Kate shocked the assembled when, during the pledge session where individuals stated what they would donate to the NAWSA, she sent a not the stage that included a check for $10,000 ($244,568 today). Even NAWSA president Anna Howard Shaw was temporarily stunned into silence when she opened the black-bordered envelope. Kate’s accompanying note said: “Dear Friend – the officers and members of the suffrage clubs of New York, including especially the Buffalo Suffrage Club, owe another debt of gratitude to our beloved Susan B. Anthony. Her expressed wish to you that the National American Woman Suffrage Association should be held in the Empire State, and in the city of Buffalo, the year that commemorated the sixtieth anniversary of the first Equal Rights Convention was accepted… In memory of Susan B. Anthony, will you please accept the enclosed check for $10,000, to be used as the national officers deem best in the work so dear to her and to all true lovers of justice, the enfranchisement of women….” Anyone who did not know her name knew it now.

|

In 1910, she was treasurer of the Buffalo Political Equality Club. She organized a suffrage conference in Geneva where she was now enjoying her summers at Bellwood. She also responded to a tart note by Maria Love in a Buffalo newspaper with a detailed rebuttal of the social good Buffalo suffragists were doing. |

She had not forgotten her roots in Nunda and, in 1911, she notified the village that she wished to build a library there. In her written offer to Captain H. W. Hand, Acting Librarian, she had conditions. “Dear Sir – It gives me satisfaction to announce to you, as librarian of the Nunda Library, my desire erect a library building in Nunda. With this offer there are a few conditions. It must be named the Bell Memorial Library. My desire is to have a board of five trustees, two of them women, to be elected by members of the Library Association, they to hold office for one, three and five years. I also should wish my son, Alfred George Lewis, a life trustee, he to appoint his successor. I offer this building to the people of Nunda in memory of my father, Alfred Bell, my mother, Juliette Dibble Bell, and my brother, Frederick Alfred Bell.”

Bell Memorial Library, Nunda. Image source: author photo

Theodore Roosevelt had decided to run for president as an independent through his Bull Moose Party in 1912. Kate Lewis’ commentary on his candidacy was harsh, claiming that he had never paid attention or supported woman suffrage and nobody should be fooled by his lip service. The Buffalo Express editorial staff agreed with her. And the Pittsburgh Sun, in its suffrage edition, featured a photo of Kate Lewis (the only one ever to appear publicly) along with her statement that she had been a suffragist since age 16, “as I believe in truth, liberty, and justice."

Buffalo’s anti-suffragists primarily used out-of-town speakers to make public pronouncements and, in 1913, Kate responded to one of these and used her sheep farming experience in Geneva to illustrate her point. “Lately I have become a farmer and for a time my object lessons were experimental. I knew sheep would fertilize my poor land, deep plowing and harrowing would mellow the soil and with selected seed, careful cultivating, in time, with rotation, my crops would satisfy my eyes and that I should reap a large harvest. Suffrage is like my farm: prejudice had to be overcome, long years of toil had to be endured, much service and money had to be given. When the soil was stirred to its deepest depths and some of the seed sown then the leaders who have ‘passed the bar’ began to see a little of the fruits of their labor; then other leaders arose to carry on the pioneer work.”

That year she penned another letter urging people to come out at night to hear Carrie Chapman Catt speak in Buffalo. The next year she writes urging men to support enfranchisement of women. Her last letter to the editor came in 1915. Like all mainstream suffragists, she opposed the increasingly radical noises coming from New York City, and she names Alva Belmont and the Congressional Unionas the instigators. “True suffragists in this country are non-militant and use non-militant methods.”

Kate Lewis was 67 years old in 1915. There is no further public mention of her activities for suffrage. In later years, Buffalo’s suffragists remembered her as “Lady Bountiful” for the financial support she continually provided the cause.

Bellwood, Geneva, today. Image source: Richard Palmer

The work she began in 1905 when she purchased Bellwood along Preemption Road outside Geneva had been her summer home project and the results were hers alone. She determined to have a Shropshire sheep farm. To that end, she had Norman-style sheep barns constructed and hired a professional shepherd to manage the flock. It was said of her that she was expert in her knowledge of architecture. She expanded the original Greek Revival cobblestone house, built in the 1830s; the cobblestone and mortar duplicates the original seamlessly. Two gravel pits were near the home and she had these made into elaborate sunken gardens. Flowers and trees were paramount, but she also had vegetable gardens, pergolas with vines, a greenhouse. To maintain these she had seven gardeners. The farm also had a power house and pumping station. In 1908 she had three homes built on the property to house permanent employees, and also a boarding house for single men. By this time she had expanded the original 150 acre property to 600 acres of farmland.

To work her crop lands, she had a superintendent to oversee it, but she was also important in the decision-making regards the farm. She consulted with the organization that predated the Cornell AgriTech college to learn the latest techniques in crop improvement.

Like all farmers, she had to deal with the vicissitudes of nature. In 1911, some of her barns were destroyed by fire and in 1912 the cyclone that came through the area damaged some of her trees and crops. She eventually transitioned from sheep farming to Hereford cattle and fruit orchards.

In 1930, Katherine Bell Lewis died from injuries suffered in a carriage accident on Preemption Road, not far from her beloved Bellwood. She was 82 years old.

Kate had been in charge of the Buffalo Almshouse Nursey for 12 years, was one of the founders of the Buffalo Children’s Hospital. At the time of her death, she owned both Elmstone in Buffalo and Bellwood in Geneva. Her estate was valued at over $2,000,000, most of that consisting of General Electric stock. Her will left the bulk of her estate to her son Alfred, with bequests to grandchildren, a long time family retainer, $20,000 ($46,338)each to Westminster Presbyterian and Children’s Hospital. But the most interesting bequest is the one to her daughter-in-law and fellow suffragist, Agnes Slosson Bell: $202,602, today’s equivalent of $4,694,185. Kate understood the power of putting money into the hands of intelligent women and trusting them to do good with it. She led by example.

Portrait of Katherine Bell Lewis, on view in the Bell Memorial Library. Image photographed and restored by the author.

To learn more about Elmstone, look here. To learn more about the Niagara Hotel, look here.

Emmeline Pankhurst. Image source: Wikimedia.

Emmeline Pankhurst. Image source: Wikimedia.